Ruth Kotinsky made a number of important contributions to thinking about lifelong learning and welfare. Of particular interest was her exploration of adult education as an aspect of everyday life and working together to build a life in common.

contents: introduction • life and contribution • adult education and the social scene • the nature of adult education • the social scene and ‘making a life in common’ • collective action • worthwhile work • the problem of schooling • process • why is the book ignored? • conclusion • further reading and references • acknowledgements • how to cite this piece

Ruth Kotinsky (1903-1955) holds a special, but often overlooked, place in the development of thinking around adult education and lifelong learning in the United States. The emerging vision of adult education as a field of practice and study found a voice in the writings not only of Eduard Lindeman in the USA and Albert Mansbridge and Basil Yeaxlee in the UK but also in the work of Ruth Kotinsky. In addition, she made a significant contribution to thinking about secondary and early education in the USA, and later to the discussion of mental health and delinquency. Norma Nerstrom (1999) has summed up her work as follows:

[She] was highly creative and possessed the rare quality of applying the findings of others to achieve a creation that was distinctly her own. She postulated that education was a continuous process from cradle to grave and her work reflected this belief. Ruth Kotinsky took pleasure in the written word and used it as a vehicle to share the learning experiences of her vastly interesting career. She recognized a strong connection between education and mental health, which has been documented in much of her work.

In this piece, we will examine the special contribution she made – particularly in Adult Education and the Social Scene.

Life and contribution

Ruth Kotinsky was born on August 23, 1903, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her father, Jacob Kotinsky (1873-1928) was an entomologist. Both he and her mother, Sarah Levin (1878-?), were from Russia. He was one of the early settlers in Woodbine, New Jersey. The township had been founded in 1891 as a community for Russian and Polish Jewish immigrants (Kempler 2016). Jacob arrived in the USA in 1888, and worked in factories and farmed with his father. According to an exhibit in the Sam Azeez Museum of Woodbine Heritage, he had ‘worked hard to educate himself…and others, opening a library and night school’. Jacob Kotinsky went on to Rutgers University, and after graduating, returned to Woodbine to teach at the local Agricultural School.

Later, Jacob became one of the USDA’s first entomologists and worked in the territory of Hawaii (Friedenwald 1912. Mitchell 1966). However, his political activities appear to have disrupted this. In 1910 he helped to organize a movement in aid of Russian labourers in Hawaii, ‘said to be held in peonage by the managers of the sugar plantations in the Islands’ (Sunday Advertiser, Honolulu, June 12). The report continues, ‘steps were taken to prevent him and others from approaching the Russians… Later, Kotinsky was allowed to resign from his position and denials were given out that his retirement and his socialism were related’).

It looks like the family moved around.

The YMCA and adult education

After leaving Wisconsin, Ruth Kotinsky worked for the National YMCA in New York – undertaking research, preparing for conferences and editing research findings (Neerstom 2015). It was something of a classic route for those concerned with deepening adult and informal education practice – Eduard Lindeman, Robbie Kidd, Basil Yeaxlee and Malcolm Knowles all worked for the YMCA at some point in their early careers. Her choice of college for her PhD studies was also propitious. She went to Teacher’s College, University of Columbia and had William Heard Kilpatrick – a great advocate of Dewey’s thinking – as her mentor and professor. Her first book Adult Education and the Social Scene (1933) was largely based on her dissertation (also completed in 1933). As we will see, it was a landmark text.

The contribution of the YMCA to the provision of adult education was one of the next areas of exploration (Kotinsky 1936). Later she also wrote two books for the American Association for Adult Education. The first explored the role and possibilities of adult education councils and the significant problems faced when trying to focus the different elements of the adult education movement on the realization of democratic values (Kotinsky 1940: 161-7).

Ruth Kotinsky also edited The Educational Council Bulletin (concerned with the professional development of group leaders and workers) and was on the editorial board of Adult Education Bulletin published by the National Education Association (1936-8).

Parent education and the secondary school curriculum

After working for the YMCA Ruth Kotinsky had joined the National Council of Parent Education (editing the journal Parent Education) and was asked to explore matters deemed to be of particular concern. An example of this work concerned the function of public libraries in parent education programmes. Having used questionnaires to examine the views of public librarians and parent education workers, she and Elizabeth M Smith (from Albany NY Public Library) brought together the parties in a round table discussion to explore the findings (see Smith 1937).

She was to work next with Commission on the Secondary School Curriculum where she contributed to a number of important works (see, for example, Thayer et. al. 1939).

Elementary adult education

Kotinsky turned next to the state of elementary education for adults (1941). The American Association of Adult Education had hired her as an editor and research director. At this point, she was particularly concerned with the state of the literacy programmes aimed at immigrants. Critical of notions such as ‘Americanization’ and of the lack of meaningful educational opportunities open to those labelled as ‘underprivileged’, Ruth argued that programs and practice should be framed within the concerns of the new adult education movement. In Elementary Education of Adults she argued opportunity should be open to all:

… no matter how ample their educational background, to develop further as human beings – to learn to live more richly as individuals and to cooperate more intelligently in conducting their common affairs. (1941: xi)

She continued:

Viewed in this light, how adequate are the reading and writing, citizenship training, and Americanization programs originally devised to help ‘unfortunates’ compensate for their deficiencies?. What reconstruction is required in these programs if their outcomes are to be commensurate with the scope and social signficance of the problems they seek to solve?

Subtitled ‘A critical review’, Kotinsky drew a bleak picture of the direction and nature of the work undertaken in the sector. Uninformed by educational theory, lacking in psychological understanding, and concerned more with the ‘cultivation of correctness of speech’ and with ‘food, clothing, grooming, housekeeping, child-rearing, (so-called ‘women’s business’) (1941: 28-9), programs failed to look to flourishing and cultivating democracy.

Ruth Kotinsky continued to work with AAAE until 1955 when she joined the Family Service Association of America as a research director. Malcolm Knowles remembers her as someone ‘who stayed pretty much in her office in New York writing impressive articles and books’ (see Hilton 1982: 12). She lived in Manhattan for much of her time in New York (1930 and 1940 Census returns). In 1948 she was based at 62 W. 91st St close to Central Park (Schoenfeld 1948). We know very little about her private life.

Children, young people and mental health

Kotinsky gained particular recognition through her contribution to The 1950 White House Conference on Children and Youth. It is said to have been a major step toward a nationwide effort to deal with one of the most important problems of the decade:

How can we develop in children the mental, emotional, and spiritual qualities essential to individual happiness and responsible citizenship? What physical, emotional, and social conditions are necessary to this development? (Childrens’ Bureau 1967)

She had forged a fruitful relationship with Helen Leland Witmer. Witmer had worked as a teacher, trained as a social worker (Bryn Mawr College) and completed a PhD at the University of Wisconsin (a few years after Ruth Kotinsky was there). For twenty years (from 1929,) Helen Leland Witmer had been director of research at Smith College’s School of Social Work in Northampton, Massachusetts, and had then moved to the University of California as a professor of social welfare. She was also the director of the fact-finding for the White House Conference on Children and Youth (Manelius 2007). In 1951, she became director of the Division of Research for the U.S. Children’s Bureau in Washington. Witmer and Kotinsky’s collaboration resulted in two important publications: Personality in the Making (1952) and Community Programs for Mental Health (1955).

Final days

One of Kotinsky’s last pieces of work was to plan and chair a major conference exploring new perspectives on research into juvenile delinquency. The thinking of Erik Erikson and Robert Merton – who both participated – provided the starting point for deliberations (see Kotinsky and Witmer 1956). Martha M Eliot (Chief, Children’s Bureau) commented that report of the Conference was ‘characteristic of Ruth Kotinsky’s many contributions to mental health and education’.

She was always trying to arrive at general principles through some new synthesis of theories and points of view of a variety of disciplines—education, mental health, child development, parent, education. In building a bridge between psychological and sociological theories about delinquency, this report represents a change in orientation for delinquency research. And it is for this reason that the report of this conference has special urgency for workers in universities and research centers conducting research in this or related areas. (Eliot in Kotinsky and Witmer 1956: ii-iii)

Ruth had died in Englewood, New Jersey (across the Hudson River from Manhattan) on November 27, 1955. She had been involved, as a passenger, in a road traffic accident.

Adult education and the social scene

Writing in the American Journal of Sociology, Alexander Meiklejohn (1935) describes Adult Education and the Social Scene as ‘an excellent statement of a significant point of view’. He continues:

It is dialectical in method, keenly critical of current forms of adult teaching, and especially of the ideas, or lack of ideas, underlying them. The demand that the adult teacher see clearly what he has to do, and do it, is vigorously and vividly made.

According to Ronald Hilton, the book is ‘one of the most innovative and thought-provoking books of the entire history of adult education’ (1982: 13). He continued:

More than any book of the period, it couples a thoughtful appraisal of what adult education might hope to provide to Americans with a careful caveat of what it had better not try to become. She cautions against overstating the case, against promising more than can be delivered, and of falsely imitating such other professions as medicine or law.

Norma Nerstrom (2013: 160) has also argued that Ruth Kotinsky’s work was ahead of its time.

Long before Jack Mezirow (1978) identified perspective transformation, Stephen Brookfield (1995) wrote about challenging the status quo, or John Dirkx (2008) realized the importance of affective learning, Kotinsky recognized and documented these principles as being critical elements in the field of adult education. These observations are strongly demonstrated throughout her work.

The question then becomes, why has the book been paid so little attention? Before trying to answer this question, I want to highlight some key themes in the book.

The nature of adult education

Kotinsky begins the book by stating that adult education ‘is here conceived as an essential component of any effort toward a more desirable social order’ (1933 xiii). In arguing this she, like Eduard Lindeman before her, drew heavily upon the work of John Dewey. She viewed education as a social process – ‘a process of living and not a preparation for future living’ (Dewey 1916). This process entailed the enlargement and emancipation of experience (Dewey 1933: 340). Unlike Lindeman in his classic discussion of the meaning of adult education (1926), Ruth Kotinsky took time to discuss the nature of adult education. She did so, in part, because she believed that the adult education movement in the USA had ‘deliberately refrained from definition’ (1933: 3) and this was getting in the way of developing understanding.

No one thought seems to emerge more frequently in the discussion than that life is progressive: adulthood is not something new after childhood and youth, but grows out of them and is of the same nature. Wisdom does not come suddenly to the adult. No more does emotional adequacy, moral insight, or an attitude of responsibility. They must each be practised during childhood and youth in order to be present during later years. And they must not only endure, but be practised in more and more situations, as the stream of life develops. There is no stopping place with a signpost to mark maturity.

The only distinguishing characteristics of adults are their longer experience, the difference in kind of the new experiences which they are likely to meet, and the relatively greater import of the problems which have a claim upon them, willy-nilly, ready or no….

Happenings become educative experience only in so far as some active part is taken in their direction, so that success or failure means learning for better success the next time. There must be planful doing if life is to be educative: no years of passive resignation will suffice. (Kotinsky 1933: 22-3)

In other words, Ruth Kotinsky – like Basil Yeaxlee – was concerned with lifelong education. Life must be turned into education – and schooling seen as life. This is the way, Kotinsky argues, to eradicate the problematic break between youth and adulthood (1933: 44). Her key thesis was that ‘education which does not look toward control of experience through action is pointless’ (Rosenblum 1987: 116).

‘Adult’ education is distinguished by the changing nature of experience and of the social contexts that adults inhabit (work, civil society, families etc.). The core concern of education for all ages was the same – the flourishing of all.

If an adult is a person faced with well-known but unsolved problems, and discovering always new problems as life develops and as he gains new insight into it, then an adult education worthy of the name must concern itself with helping to devise new techniques for the definition and solution of these problems, and for determining new and more desirable goals. It must not confine itself to stragglers or players by the wayside. It has an urgent and a distinctive role to play in making all the experiences of adult life meaningful, and all adult learning educative. (1933: 29).

Learning for its own sake does not exist for Ruth Kotinsky, ‘Learning has its joys for those who seek it for their purposes. Alone it is without significance’ (Kotinsky 1933: 162). Learning is also wrapped up with collective activity and social ends.

The social scene and ‘making a life in common’

Unfortunately, Ruth Kotinsky does not make the notion of ‘the social scene’ a focus for explicit discussion. The term appears just three times in the text. That said, she does make the direction of travel clear.

It is necessary… to identify adult education with social ferments, dealing with them in such ways as to make the participants intelligent and responsible planners, rather than drifters, sufferers, and undergoers merely, or ruthless schemers for personal advantage. Adult education so conceived must bide—and seize—its opportunity, and build its specific plans on the spot in the face of urgent realities and in view of educationally or socially desirable outcomes. All that can be sketched in advance is its relative task in a tumultuous scene. (1933: xv)

Try looking up ‘the social scene’ and you are likely to find either discussion of parties, club life and meeting up with others – or recipes for the use of social media in business. Kotinsky is concerned with something more fundamental – the changing nature of the human condition and the experience of being human, and living life with others, in ‘mass society’. It is something of the same territory that Hannah Arendt later explores in The Human Condition (1958|1998). Arendt argued that modernity is characterized by the loss of the world. By this she means:

… the restriction or elimination of the public sphere of action and speech in favor of the private world of introspection and the private pursuit of economic interests. Modernity is the age of mass society, of the rise of the social out of a previous distinction between the public and the private, and of the victory of animal laborans over homo faber. (d’Entreves 2019)

Homo faber is Arendt’s image of men and women ‘making a life in common’ (Sennett 2008: 6). Animal laborans refers to unfreedom – the dull and demeaning routines of labour in industrial (and post-industrial) societies. Like Arendt, Kotinsky is critical of the impact of modernity on many people’s lives – and ‘making a life in common’ is quite a good description of what she is focusing on when using the term ‘the social scene’. [See, also the exploration of Richard Sennett’s work on these pages].

Collective action – Social planning, community organization, social movements, and groups

Kotinsky’s supervisor, William Kilpatrick, was a key advocate of developing schooling to meet changing needs:

Our times are changing and-in part at least-as times never changed before. These changes make new demands on the schools. And our education must greatly change itself in order to meet the new situation…. Education is the strategic support and maker of a better civilization. (Kilpatrick 1926: 4 and 136)

However, Ruth Kotinsky was looking well beyond schooling both as an institution and a process.

Life… must be made into education. If the new movement is not to take on the bad accoutrements of the old, it must devise its own ways for providing educational experience. And, if it is to be adult education in any real sense, it must be concerned with what concerns adults. Every moment of life carries its own experience with it; at every moment the organism is in contact with its environment, interacting with it in one way or another. (1933: 46)

This inevitably took her into the world of social movements, the experiences of factories and offices, and into the realm of community organization and groups. She was writing at a time when there were considerable advances in understanding the functions and processes of groups, and their social and educative role (see Reid 1981 in the infed archives).

Rosenblum, reflecting on the significance of Kotinsky’s thinking, notes that she saw adult education’s role in identifying social problems and dealing with them in such ways as to make the participants intelligent and responsible planners. (Rosenblum 1987). This focus on social planning was both of its time and looked forward to community organization and the anti-poverty programs 1960s and 1970s. However, as Williams (1976) noted some time ago, the term ‘social planning’ is rarely defined with any precision.

There had been a growing focus on education for social reconstruction and Kotinsky shared this concern and looked to placing adult education alongside social planning (see also Herring 1933). Francis J Brown, writing a few years later, shared many of the concerns running through Adult Education and the Social Scene:

We can achieve social planning only by redefining democracy – not in terms of individual liberty and freedom of action but as it was originally and constitutionally defined-to promote the general welfare. We must recognize that the right of the individual is limited by the equal right for every other individual; that freedom does not imply the right to deprive others of the “inalienable right of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” (Brown 1936: 941)

Kotinsky understood the significance of much adult education activity being based in social movements like that of her employer the YMCA. They were part of civil society. They were not the state, nor were they industry. They offered the chance that ‘Profit’ could be supplanted by growth for the producers and consumers of goods (1933: 65). Like Eduard Lindeman and Mary Parker Follett, Ruth Kotinsky looked to community organization and strengthening the capacity of people to work together for change.

The training for the new democracy must be from the cradle – through nursery, school and play, and on and on through every activity of our life. Citizenship is not to be learned in good government classes or current events courses or lessons in civics. It is to be acquired only through those modes of living and acting which shall teach us how to grow the social consciousness. This should be the object of all day school education, of all night school education, of all our supervised recreation, of all our family life, of our club life, of our civic life. (Follett 1918: 363)

One of the fascinating aspects of Kotinsky’s approach is that she looks to the influences ‘forming adult life’ and the contribution and possibilities of different institutions. She explores, for example to the developmental possibilities of family welfare agencies and, medical professions as well as civil society – churches, service clubs, women’s clubs etc. She understood that adult educators had a lot to learn from social work in the USA and the then growing understanding that there had to be a focus on casework, group work and community organization. Crucially, she looked to impact of industrial processes and products and the world of work. It is interesting that Follett does not talk about work in the quotation above. Kotinsky appreciated that people’s changing experience of work could be both a spur to, and focus for, developing new understanding. The workplace had to be a critical site for tackling social issues (see Heaney 1996).

Worthwhile work

If leisure is to be worthy, it must be purposive and creative; and labor, to be worthy, must be the same; and the good leisure cannot be had without the good labor. The devil may make work for idle hands, but the more so if the hands have been busy at devil’s work all day. (Kotinsky 1933: 152-3)

One of the striking features of Kotinsky’s approach is that she takes the world of work head-on. She also makes the quality of the experiences of work – and its products – central to her exploration and recognizes that this is fundamental both to individual happiness and wellbeing, and to building a ‘life in common’.

It has been emphasized before that the conditions of production are of great educational potentiality. Not only do the goods produced in part determine the life of the consumers, but the productive process itself in large part determines the life of the producers. Yet, with all of this, industry has almost never been seriously considered as an educational agency. There can be no doubt about its effectiveness in shaping the lives of its participants. Yet the part that it plays in changing the habits and thoughts and feelings of adults is seldom consciously analyzed, and productive experience is almost never controlled for the improvement of human life. (Kotinsky 1933: 84-5)

She takes advertising to task, for example, for setting to manipulate the adult mind – comparing it to spreading the desire for habit-forming drugs – and the distorting impact of the media. She rails against ‘overlords of one kind or another’ who direct affairs to their own advantage and ‘at best, made fumbling efforts at paternalistic betterment’ (1933: 62). Private profit and personal aggrandizement, she argues, ‘play a larger part in the determination of large events than any social motive’ (op. cit.). Importantly, Ruth Kotinsky is deeply critical of the debilitating effect the organization and ‘industrialization’ of work has upon workers and draws upon William Morris to express this.

[F]or a man to be the whole of his life hopelessly engaged in performing one repulsive and never-ending task, is an arrangement fit enough for the hell imagined by theologians, but scarcely fit for any other form of society. (Morris 1983/4)

She argues that Morris’s description of that worthy labour ‘comes perilously close’ to that of worthy leisure.

[W]ork in a duly ordered community should be made attractive by the consciousness of usefulness, by its being carried on with intelligent interest, by variety, and by its being exercised amidst pleasurable surroundings. But I have also claimed, as we all do, that the day’s work should not be wearisomely long. (op. cit.).

All this entails a radical shift in adult education – and educational institutions more generally. They cannot confine themselves to ‘the introduction of decoys away from commercialized amusement’ (Kotinsky 1933: 152).

[A]ll the time of life should be of worth, and so should be marked with those characteristics of leisure which make it now considered of greater possible worth—freedom, choice, purpose, goal in view, realization of the immediate value of experience. To the extent that work time is not marked by these, it contaminates the worth of leisure. Therefore, the planning of life should be directed toward making these the characteristics of all life activities. Such planning will mean no time to be squandered on “pastimes” except perhaps such as may be necessary to the re-creation of the organism; all other time should be devoted to the creation of a genuine culture in which learning plays its significant role, suffusing life with values to the point of artistry. (Kotinsky 1933: 171)

All this entails a particular way of ‘knowing’. It does not involve the simple application of knowledge and theory to situations (Smith and Smith 2008: 15).

The problem of schooling

Given what Ruth Kotinsky has said about the significance of experience, the nature of education and the state of society, it is not surprising that she was deeply critical of contemporary schooling. Dewey’s thinking, and Kirkpatrick’s advocacy of the ‘project method’, had been heeded by a growing number of teachers and educationalists. However, Kotinsky saw that the ‘remaking’ of schooling would take time, noting for example that routine and tradition had ‘been almost too strong for the concepts brought into the field by the kindergarten, but slowly its influence has been felt creeping up throughout the elementary school’ (1933: 37). Her hope was that schooling could be experienced as life, and life as education.

Kotinsky’s vision entailed something like the deschooling process later advocated by Ivan Illich. She suggested a shift from an emphasis on ‘indoor’ schooling to a concern with ‘outdoor’ education (1933: 77-82). Children and young people required direct experience of the world. They needed to experience and learn from the workplace, neighbourhood and civil society. Both they – and many adults – were too reliant on ‘segregated experience in isolated places for their educational work’ (1933: 78). While there is a role for reflection and learning away from certain situations, ‘it is not easy to transplant “indoor” deliberations into “outdoor” conduct’ (1933: 79). Kotinsky is critical of adult educators who try to make learning a ‘schoolish affair’ and provides a standard by which schools, colleges and organizations can judge their efforts. How do they ‘measure up as an institution for the conscious reconstruction of institutions to human ends by the humans participating in and affected by them?’ (1933: 82).

How are these changes in schooling to be achieved? She was hopeful that changes already in train in schools would continue and she also saw that broader shifts in society would have an impact. One of these lay in the development of the adult education movement.

[I]f active participation and keenly felt responsibility for associated living were made actual among adults, schooling would probably not remain abstract in its dealings with politics, civics, and wider social relationships— might cease trying to talk about civic life in favor of being active in it. (1933: 39)

Process

There are considerable dangers in transplanting old conceptions from the schooling of children into adult learning – and into the exploration of experience in general. There needs to be a move away from ‘delivering’ curricula. ‘There is a new, much wider, and far more difficult task for it to perform…, i.e. that all group life, no matter where, shall have educational value to the participants as its prime objective’ (Kotinsky 1933: 174).

The classroom teacher can come to her school a week before her pupils and lay the stage in a way which she feels will give rise to educative activities on the part of her pupils. The adult educator finds the stage already set, and in ways none too propitious for the ends he has in view. It is one of his functions to consider that stage and seek in it those elements which are educative, and those which can be changed in desirable directions. This is no mere matter of beginning a week or two in advance of a class convening on the first Monday night in October. It means that a whole new set of investigations must be instituted, and a whole new set of techniques developed. The desirable and more easily controllable elements in the gigantic network of social life must be discovered and tentative techniques elaborated for introducing into them a consideration of their educational value. (1933: 175)

The orientation here is very much in the tradition of informal education. It is pedagogy rather than diadactics (Smith 2019). This involves attention to process and the knowledge and capacity to help individuals and groups to make sense of their experiences and to act. ‘The whole argument of these pages’, Kotinsky wrote, has been that:

… education which does not look toward control of experience through action is indeed pointless. It is not the action which is to be scorned, but the determination by the teacher in advance of what the action is to be. It is the difficult task of the adult educator to help persons to become conscious and good schemers of their own destinies without determining these destinies for them. His one doctrine is that the destiny which is controlled and sought is better than the destiny of an accepted fate. (1933: 179)

This entails a particular orientation on the part of the educator (see the discussion in What is pedagogy?) and an appreciation of ‘the social scene’. It also involves attention to process and ability to facilitate and intervene in group life. Understanding of such processes and the nature of work with groups was going through a period of particular development at the time that Ruth Kotinsky was writing Adult Education and the Social Scene. She went on to deepen her awareness of psychological processes in her later career – and it would have been fascinating if she could have had the opportunity to revisit these concerns in later life.

Why has the book been paid so little attention?

It is not difficult to identify possible reasons why Adult Education and the Social Scene has remained a largely undiscovered ‘classic’. Weighting them is quite another matter.

First, Kotinsky was writing as a woman in a largely male field. Most of the books produced about adult education at this time came from the pens of men (and were probably typed by the fingers of women). One also suspects that her gender impacted on her employment. She had to rely on a series of posts and projects with third sector and state organizations. The world of tenured posts in universities was not easily available to her.

Second, her political orientation can read as radical. This combined with her criticism of Americanization and a Russian (Jewish) name may well have led to her work being pushed to one side without much reflection by a large group of a number of people around the adult education field in the United States. Eduard Lindeman faced a similar situation in some respects.

Third, this book was not written with a classic adult education orientation. It was not concerned with developing a profession but with how education can become part of living. This is far more the domain of informal education and social pedagogy traditions. She also looked to learning from social work and other traditions of practice.

Last – and linked to the first point – Ruth Kotinsky moved from project to project and so did not return in a comprehensive way to the practice of adult education and learning. Compared with Eduard Lindeman and Malcolm Knowles, for example, she did not have a concentrated body of writing about the area.

Conclusion

Where writers have used Ruth Kotinsky’s work in more recent times, they have sometimes made a link to Paulo Freire and his concern with praxis. While there is a rather obvious parallel to her emphasis on action, and what can be read of her political orientation, it is rather short-sighted to stop at that. If we want to make a connection to more contemporary theorists, a much better case can be made for Ivan Illich. Many of his interests – deschooling, the nature of work, community organization and conviviality – mirror those of Kotinsky. He too continues to be overlooked after his death. Their neglect is particularly sad as their thinking retains considerable potential for those wanting to build educational forms that are more fully human, and communities that allow people to flourish (Finger and Asún 2001: 14-15).

Perhaps the best way to finish is to quote Ruth Kotinsky’s own conclusion:

Adults have the opportunity to build the world that they want through the control of their adult experience. Their education must somehow help them to determine what is good, and how to take hold to attain the next level. The process is not only continuous with life, but continuous with the life of civilized man. There is no specifying in advance what adult education shall do here or there… The minutiae, even the broad lines of advance, must be mapped on the terrain itself, but never out of sight of the chief goal—the improvement of adult life through the increased control by adults over their experience. (1933: 191)

Bibliography and further reading

Arendt, H. (1958|1998) The Human Condition. 2e. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brown, F. J. (1936). Social Planning Through Education, American Sociological Review 1: 6 (December): 934-942. [JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2084618. Retrieved January 31, 2021].

Childrens’ Bureau (1967). The Story of the White House Conferences on Children and Youth. Washington DC.: U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Social and Rehabilitation Service, Children’s Bureau.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. An introduction to the philosophy of education (1966 edn.). New York: Free Press.

Dewey, J. (1933). How We Think. A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. (Revised edn.). Boston: D. C. Heath.

Ely, M. L. (ed.) (1936). Adult Education in Action. New York: American Association for Adult Education.

d’Entreves, M. P. (2019). Hannah Arendt, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/arendt/. Retrieved March 2, 2020].

Finger, M. And Asún, J. M. (2001). Adult Education at the Crossroads. Learning our way out. London: Zed Books.

Flowers, R. (2009). Traditions of popular education. REPORT – Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschung, 32(2), 9-22. [https://doi.org/10.3278/REP0902W009. Retrieved January 31, 2021].

Follett, M. P. (1918). The New State – Group Organization, the Solution for Popular Government. New York: Longman, Green and Co.

Follett, M. P. (1924). Creative Experience. New York: Longman Green and Co (reprinted by Peter Owen in 1951).

Friedenwald, H. (ed.) (1912). The American Jewish Yearbook 5673. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America. [https://www.ajcarchives.org/ajc_data/files/vol_14__1912_1913.pdf. Retrieved January 31, 2021].

Heaney, S. (1996). Adult Education for Social Change. From Centre Stage to the Wings and back again. Columbus, OH: ERIC Monograph. [https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED396190. Retrieved January 31, 2021]

Herring, J. (1933). Social Planning and Adult Education. New York: The Macmillan Company.

Hilton, R. (1982). Humanizing Adult Education Research. Five stories from the 1930’s. New York: Syracuse University Publications in Continuing Education.

Illich, Ivan (1973). Deschooling Society. Harmondsworth: Penguin. (First published by Harper and Row 1971; now republished by Marion Boyars).

Imel, S. and Cersch G. T. (eds.). No Small Lives: Handbook of North American Early Women Adult Educators 1925-1950. Charlotte, NC.: Information Age Publishing.

Imel, S. and Cersch, G. T. (2008). “What Happened to the Women? An

Analysis and Discussion of Early Women Adult Educators,” Adult Education Research Conference. [https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2008/roundtables/4. Retrieved December 7, 2020].

Kempler, C. (2016). Community Honors Its Heritage and Ecumenical Spirit, B’nai B’rith International. [https://www.bnaibrith.org/digital-exclusives/community-honors-its-heritage-and-ecumenical-spirit. Retrieved: December 9, 2020].

Kilpatrick, W. H. (1926). Education for a Changing Civilization. New York: The Macmillan Co.

Kotinsky, Ruth (1933) Adult Education and The Social Scene. New York: D. Appleton-Century Co.

Kotinsky, Ruth (1936). The YMCA in Ely, M. L. (ed.) (1936). Adult Education in Action. New York: American Association for Adult Education.

Kotinsky, Ruth (1940) Adult Education Councils. New York: American Association for Adult Education.

Kotinsky, Ruth (1941) Elementary Education of Adults, A Critical Interpretation, New York: American Association of Adult Education.

Kotinsky, Ruth (1941). For Every Child—A Fair Chance for a Healthy Personality.

Kotinsky, Ruth and Witmer, Helen L. (1955) Community Programs for Mental Health Theory, Practice, Evaluation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (Published for the Commonwealth Fund).

Kotinsky, Ruth, Sonquist David E., Soares, Theodore G. and Huff, LeRoy (1930) ‘Some wider functions of adult education’, Religious Education 25(7).

Lindeman, E. C. (1924) Social Discovery. An approach to the study of functional groups, New York: Republic Publishing.

Lindeman, E. C. (1926a) The Meaning of Adult Education, New York: New Republic. Republished in a new edition in 1989 by The Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education.

Manelius, L, (2007). Helen Leland Wittmer, Pennsylvania Center for the Book. [https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/bios/Witmer__Helen. Retrieved November 14, 2020].

Midcentury White House Conference on Children and Youth (1951). A Healthy Personality for Every Child: A Digest of the Fact-Finding Report to the Midcentury White House Conference on Children and Youth. New York: Health Publications Institute.

Mitchell, W. C. (1966). History of the Department of Entomology, University of Hawaii, College of Tropical Agriculture, ScholarSpace at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa. [https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/5100180.pdf. Retrieved November 3, 2020].

Meiklejohn, A. (1935). Review of Adult Education and the Social Scene, American Journal of Sociology 41: 1 (July). [https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/217047. Retrieved October 12, 2020]

Morris, W. (1883/1884) Useful Work Versus Useless Toil. Lecture given in various places and then published 1885 – London: Socialist League Printery. [https://www.marxists.org/archive/morris/works/1884/useful.htm. Retrieved January 28, 2021].

Morris, W. (1884). A Factory As It Might Be. First published in Justice, April-May 1884. Reproduced in the informal education archives. [https://infed.org/mobi/william-morris-a-factory-as-it-might-be/. Retrieved January 28, 2021].

Nerstrom, Norma (1999) ‘Ruth Kotinsky’, ACE Resources, National-Louis University, http://www.nl.edu/academics/cas/ace/resources/ruthkotinsky.cfm. Accessed: February 6, 2005.

Nerstrom, N. (2015). Ruth Kotinsky. Glancing back, reaching forward, in Imel, S. and Bersch G. T. (eds.). No Small Lives: Handbook of North American Early Women Adult Educators 1925-1950. Charlotte, NC.: Information Age Publishing.

Rosenblum, Sandra. Book review in “1926-1986: A Retrospective Look at Selected Adult Education Literature,” edited by Ralph Brockett. Adult Education Quarterly. 37, no. 2 (Winter 1987): 114-121.

Sam Azeez Museum of Woodbine Heritage (undated). Woodbine Success Stories – Jacob Kotinsky. [https://www.thesam.org/kotinsky.htm. Retrieved December 9, 2020].

Sennett, Richard (2008). The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Schoenfeld, Clay (ed.) / Wisconsin alumnus Volume 50, Number 1 (Oct. 1948) [http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/UW/UW-idx?type=turn&entity=UW.v50i1.p0052&id=UW.v50i1&isize=text. Retrieved December 8, 2020].

Smith, E. M. (1937). Parent Education Round Table, Bulletin of the American Library Association, 31 (11), Proceedings of the Annual Conference (OCTOBER 15, 1937), pp. 816-818. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/25689225. Retrieved December 8, 2020]

Smith, H. and Smith, M. K. (2008). The Art of Helping Others. Being around, being there, being wise. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Smith, M. K. (2012, 2019). ‘What is pedagogy?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-pedagogy/. Retrieved: February 15, 2021].

Thayer, V. T., Zachry, Caroline B. and Kotinsky, Ruth (1939) Reorganizing Secondary Education. Prepared for the Commission On Secondary School Curriculum, New York: Appleton-Century.

Whipple, C. A.and Kotinsky, Ruth (1942) Practical methods in adult education, New York: Bureau of Adult Education, New York State Education Department.

Williams, R. (1976) The idea of social planning, Planning Outlook, 19:1-2, 11-18. [DOI: 10.1080/00320717608711516. Retrieved January 31, 2021].

Witmer, Helen L. and Kotinsky, Ruth (eds.) (1952) Personality in the Making: The Fact-Finding Report of the Midcentury White House Conference on Children and Youth. New York: Harper & Row.

Witmer, Helen L. and Kotinsky, Ruth (eds.) (1956) New perspectives for research on juvenile delinquency: a report of a conference on the relevance and interrelations of certain concepts from sociology and psychiatry for delinquency, held May 6 and 7, 1955, Washington: U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, Social Security Administration, Children’s Bureau.

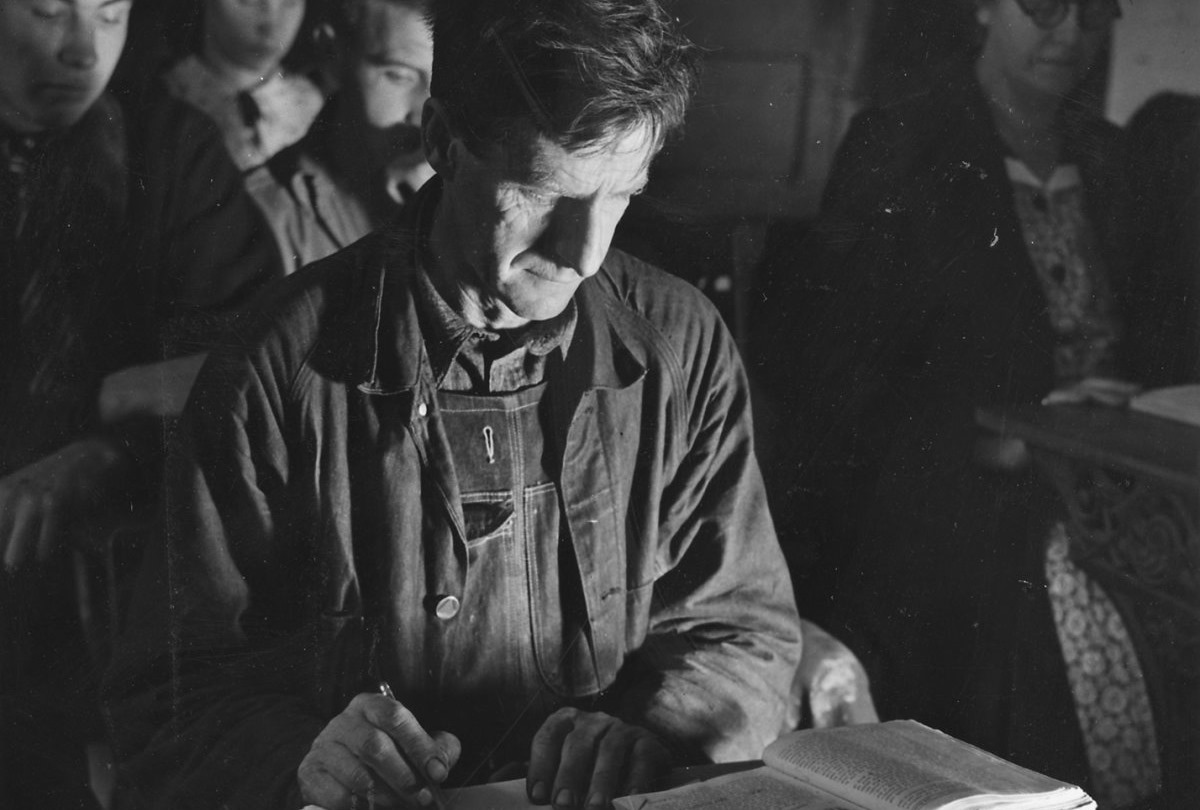

Acknowledgements: Picture: National Archives and Records Administration. WPA Adult Education (New Deal). Believed to be in the public domain (sourced from Wikimedia). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WPA_Adult_Education_-_NARA_-_195909.tif.

Picture: Ruth Kotinsky as a member of the class of 1923 is from the University Wisconsin publication, The Badger. Believed to be in the public domain.

Cover Useful Work vs. Useless Toil – The William Morris Gallery has in its collection various versions of this pamphlet including this one published in 1898 and illustrated by Walter Crane (1845 – 1915). Believed to be in the public domain.

An earlier and much shorter piece on Ruth Kotinsky was published on infed.org in 2005.

How to cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2021) ‘Ruth Kotinsky on adult education and lifelong learning’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/ruth-kotinsky-on-adult-education-and-lifelong-learning/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K. Smith 2021